What is “Whole Community”? Why is it important? _review

Carrie: Welcome! As early as your first visit we started talking about “whole community” planning, which is an attitude and way of doing things. Whole community plans apply to an entire community, strengthen community resilience, and help communities bounce back quickly after disaster strikes.

Good communication is an important part of whole community.

FEMA says the phrase “whole community” means involving people in the development of national preparedness document and ensuring their roles and responsibilities are reflected in the content of the materials.

As you work on whole community planning, you may get to know community members or groups that you didn’t know before. Part of respectful collaboration is checking with community groups about how they prefer to be identified.

One partner that may be new to you is the Partnership for Inclusive Disaster Strategies, a national organization that addresses needs of people with disabilities before, during and after disasters and emergencies.

Communication is also important with partners. The Action Team will communicate with local planners before emergencies at Action Team meetings and other times. Using our Kick Start Directory tool may help you create and sustain stronger community partnerships. But what about when disaster strikes?

Communication between a disability organization and local emergency management and public health during an emergency may be different for each community. For example, some communities may give emergency instructions by radio. Some communities may want to use a communication type besides 9-1-1.

Disability organizations should ask local planners:

· How will you be sharing information with community organization like ours during a disaster, disaster and pandemic?

· How would you like community organizations like ours to communicate with you during an emergency, disaster or pandemic?

Disability organizations should ask local planners: We know that you would like everyone to be ready for an emergency, disaster, or pandemic. But if a person with a disability needs help during an emergency, disaster or pandemic, who should they contact? The answer to this question may be different in each community.

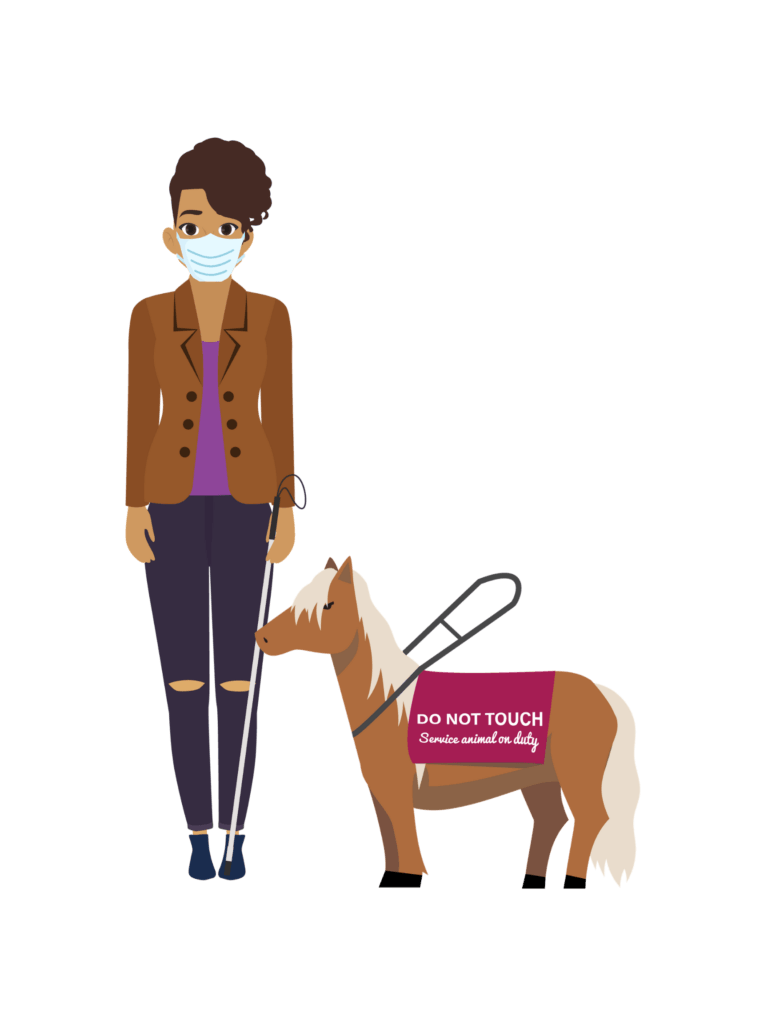

EM: Remember when you met César when we were out and about? He told us that he was on vacation in Faraway County when disaster struck. He made it to the emergency shelter, but they didn’t allow his service animal, Ginger, to stay with him. He asked you to imagine the impact of separating him from Ginger.

César said he was usually very independent. He lives alone, rides public transit to and from work and all over the city. He’s used to a lot of independence. Without Ginger, he lost a lot of his independence. He needed a lot more help than usual. César said he was humiliated. He had to get help to go to the bathroom and lunchroom. The shelter workers were so busy they didn’t have time to help him. He had to wait an hour to go to the bathroom. He was right to be angry.

Think about César and Ginger again. Separating people from their service animals in shelters was a Faraway County emergency policy. The policy protects people with animal allergies or fears.

This policy is:

An example of whole community planning and likely an Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) violation

Not quite. Wouldn’t separating Cèsar and Ginger cause Cèsar to lose a support he relied on to maintain his independence? Would that be equitable?

An example of whole community planning and not likely an Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) violation

Not quite. Wouldn’t separating Cèsar and Ginger cause Cèsar to lose the support he relied on to maintain his independence? Would that be equitable?

Not an example of whole community planning and not likely an Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) violation

Not quite. Wouldn’t separating Cèsar and Ginger cause Cèsar to lose a support he relied on to maintain his independence? Would that be equitable?

Not an example of whole community planning and likely an Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) violation.

That’s right. A policy that separates disaster survivors from their service animals is not an example of whole community planning. The whole community means planning by everyone, including the general public, businesses, non-profit organizations, and all levels of government to increase coordination and better working relationships. The whole community means planning with functional and access needs in mind. It violates the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) to separate an owner from their service animal and it deprives Cèsar of support that helps him maintain his independence.

EM: A policy that separates disaster survivors from their service animals is not an example of whole community planning.

The whole community means planning by everyone, including the general public, businesses, non-profit organizations, and all levels of government to increase coordination and better working relationships.

PJ: Participation of the whole community means equal access to local, state and national preparedness activities and programs without discrimination. It means meeting the equal access and functional needs of all individuals. And it also means consistent and active participation in all aspects of planning.

Community and individual readiness for emergencies are key.

Carrie: We said that this policy violates the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the key civil rights law for people with disabilities. Under the ADA, state and local governments must provide physical access, program access, and access to effective communication in their services, including emergency planning. All of these must be included in emergency planning.

? Think about the policy again. Which is (are) the strongest ADA argument(s):

César was denied equal program access

That’s right. Under the ADA, people with disabilities are entitled to program and physical access and access to effective communication. Think about César’s situation. Program access means that a state or local government’s services, programs, and activities, when viewed in their entirety, must be readily accessible to and useable by individuals with disabilities. This means that program access decisions are made by looking at the whole service, program or activity, not just one part of it.

Without Ginger, César wasn’t able to move around independently. He couldn’t participate in the services the emergency shelter offered, such as meals in the lunchroom, with his usual level of independence.

César was denied equal physical access

That’s also right. We could also say that while the emergency shelter building and spaces inside may have been physically accessible when Ginger couldn’t be with him he lost his ability to independently access them. So without Ginger, César couldn’t keep his usual level of independence. We could also say that while the emergency shelter building and spaces inside may have been physically accessible, when Ginger couldn’t be with him, he lost his ability to independently access them.

César was denied access to effective communication

Not quite. In our scenario César was able to understand when he was told that Ginger couldn’t be with him in the shelter. He would have been able to protest that decision by speaking with shelter officials.

Now think about a new situation. Suppose there was smoke in the emergency shelter, but the alarm was broken and didn’t sound. Nobody told César about the smoke and he couldn’t smell it. If Ginger were with him and was trained to alert him to smoke, then in a sense Ginger would be needed for his access to effective communication.

? How should Faraway County change the policy that impacted César? The new policy should be:

It is the policy of Faraway County to keep people together with their service animals in emergency shelters for a fee of $10/day to cover extra cleaning costs

Not quite, try again.

It is the policy of Faraway County to keep people together with their service animals in emergency shelters

Not quite, try again.

It is the policy of Faraway County to keep people together with their services animals in emergency shelters upon written request

That’s right. An example of a whole community policy would be: It is the policy of Faraway County to keep people together with their service animals in emergency shelters. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, equal access accommodations should be free. A written request isn’t required to keep someone together with their service animal. We’ll talk more about the ADA issues on another visit.

Allen: Some counties, cities, and towns include a statement of whole community philosophy in their emergency plans.

Here are three examples:

Emergency Plan #1 Monterey, CA

To Monterey County, California, “whole community” means a strong community with residents, community leaders and government officials who actively participate in emergency planning. It means understanding community needs and how to make the community strong. The county works with different groups to strengthen what their everyday good work.

From their plan: “Monterey County has embraced FEMA’s whole community approach to creating engaged and resilient communities by which residents, emergency management practitioners, community leaders, and government officials can understand and assess the needs of their respective communities and determine the best ways to organize and strengthen their assets, capabilities, and interests. By engaging communities, we can understand the unique and diverse needs of a population…. Local capacity is built on the empowering of community members, social and service groups, faith-based and disability groups, academia, professional, private and nonprofit sectors to strengthen what works in their communities on a daily basis.”

Emergency Plan #2 Boulder, CO

Boulder, Colorado focuses on whole community disaster recovery. Boulder County feels that it’s important to plan for long-term recovery and that all stakeholders should work together on building an even stronger community.

From their plan: “By incorporating the Whole Community concept into the recovery process, communities in Boulder County can address long-term recovery in a more effective and efficient manner. All aspects of a community are needed to effectively recover….It is critical that all stakeholders work together to enable communities to develop collective, mutually supporting local capabilities to withstand the potential initial impacts of these incidents, respond quickly, and recover as rapidly as possible in a way that sustains or improves the community’s overall well-being.”

Emergency Plan #3 Miami-Dade County

Miami-Dade County, Florida focuses on community partners working together to understand community needs and organize resources to meet those needs. Miami-Dade wants to make the community stronger, with the capacity to deal with disasters.

From their plan: “The ‘Whole Community’ approach is a means by which residents, emergency management, local officials, private businesses, non-profit organizations, and faith-based organizations can collectively understand and assess the needs of their respective communities, determine the best ways to organize resources and be ready when an emergency occurs. The goal of the ‘Whole Community’ approach is to build community resilience and nurture capacity building.”

?Think about what the whole community could mean for your community. What are some examples of what that would look like?

Allen’s Response

Public health and emergency management federal and most state guidance call for whole community planning.

Partnering with local organizations is key for whole community local emergency planning.

Community organizations can:

– Provide “situational awareness” (information about what’s happening at their organization or with their stakeholders at a specific time)

– Serve as trusted communication hubs to share important emergency messages

– Host self-preparedness training

– Serve as points of distribution for emergency supplies

– Provide staging areas and reception sites (to receive disaster survivors for example)

– Support mobile feeding and transport resources

– Share COVID-19 testing and vaccine information with people served

– Provide social services such as counseling

– Provide pastoral care

– Conduct community welfare checks

Local planners benefit from:

– Shared ideas: Planners, people with disabilities, and disability organizations can learn from each other

– Shared capability: Planners can benefit from new ideas given by people with disabilities and disability organizations

– Identifying untapped community resources

Rachel: Let’s talk about some real-life situations. See the table below for some issues experienced by people with disabilities in emergency situations and whole community solutions to address the issues.

| What happened? | Why? | Whole community solution |

| People who are Deaf didn’t understand important safety information. | The local emergency plan calls for warnings by radio and bullhorn. | Multiple communication modalities for disaster warnings: • Radio • Bullhorn • County website • Texts • Qualified American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter • Closed Captioning (CC) |

| People with intellectual disabilities were evacuated to an emergency shelter. Shelter workers took away the people’s money for their own safety. | The shelter workers didn’t know that people with intellectual disabilities lead independent lives and could keep their own money. The shelter workers thought the people with intellectual disabilities needed to be protected. | Training for shelter workers so they would know to support independence for people with intellectual disabilities. |

| People were not evacuated with their wheelchairs. | The local emergency plan didn’t state the importance of keeping people together with mobility and other vital equipment. | Training for planners and first responders. Change the emergency plan to state that people with disabilities should be evacuated with their key equipment. |

| People who have sensory issues (like social anxiety or Autism Spectrum Disorder, ASD) find the emergency shelter too noisy and crowded. They may feel overwhelmed. | The shelter plan does not provide a separate quiet space in the shelter. | Planning to have a separate quiet room is an important part of a shelter plan. |