The test results are now known for the child. The second interview is being delivered at the doctor’s office. Again, we would want both parents present, along with the baby. The purpose of this interview is to give the parents the results of the chromosomal testing, which confirms that the child has the most common type of Down syndrome, trisomy 21. This interview will also allow the doctor to follow-up on the baby’s breastfeeding and any other concerns.

Archives: Lessons

Understanding Down Syndrome Copy

Mrs. Brown now has several questions about Down syndrome. Let’s continue the case to see what information Dr. Young gives the family.

Children with Down Syndrome Copy

Now, let’s continue the case study with Dr. Young by exploring the characteristics of children with Down syndrome.

Case Study: Greeting the Parents Copy

In this lesson, Mr. and Mrs. Brown meet with Dr. Young. Click on the first topic below to continue.

Best Practices for Communicating a Postnatal Diagnosis of Down Syndrome – Case Study Part 1

The doctor knows the family well. The mother, Mrs. Brown, gave birth at term yesterday to a baby boy, weighing 6 pounds 7 ounces. The doctor strongly suspects that the child has Down syndrome because of the presence of many of the physical signs, though she has not informed the family or completed any tests. This is the family’s third child; the mother is 30 and the father is 32. The other two children are 5 and 3 years of age.

In addition to receiving routine ultrasounds, the mother was offered serum analyte testing. She accepted this testing and the results were interpreted as very low risk. This is the first time that you or anyone has suspected the possibility of Down syndrome.

Continue exploring this case study by clicking on the first topic below.

Conclusion

When a couple is told there is a positive or likely prenatal Down syndrome diagnosis, it is very important for the physician to recognize the complex feelings that they have at this moment. Since the definitive diagnosis may also occur during the second trimester (though in the above case, it actually occurred in the first trimester), couples may have already developed ideas about what this particular baby will be like. A diagnosis of Down syndrome obviously alters that perception and leaves parents with conflicted emotions. Many couples will want to continue the pregnancy, no matter what, but may be afraid of what their future will bring. Others may believe that they will not be able to care for a child with Down syndrome, but are uncertain about specifics regarding termination. Still others may be torn about both options, knowing that their lives will be altered with any decision they make. Most will not know about adoption options.

Recognizing that physicians and other health care practitioners will have their own biases about what should be done, each medical provider (physicians, genetic counselors, nurses, physician assistants, etc.) needs to respond as a member of a coordinated team to individual patients in ways that reflect the patient’s values. Physicians should respond with empathy and concern as well as specific information. This type of conversation might include reference to new understandings about improved life outcomes for individuals with Down syndrome, such as their capacity to learn and become a contributing part of the larger community, and referral to local Down syndrome organizations. It also might include information on organizations devoted to adopting children with Down syndrome. However the physician or health care provider responds, the mother and father should feel understood, supported, and informed.

Your interactions with families such as this one will be remembered by them for the rest of their lives.

This video from the Down Syndrome Association of Central Ohio featuring genetics professionals in Ohio demonstrates how much more supported families can feel when they receive information, resources, and referrals to patient advocacy groups after receiving screening results. Ohio passed a Down Syndrome Information Act in 2015, and both DSACO and the Ohio State Department of Public Health recommend and disseminate our Lettercase National Center resources.

Thank you for taking the time to carefully consider your responses to these cases. We hope this module helps you as you assist other families in receiving this news.

Prenatal Testing History and Resources

Learn more about prenatal testing in the US and what types of information families and clinicians find valuable.

Other Conditions

Pregnancy screening tests do not exclusively look for Down syndrome, and they usually include a number of other conditions. Some conditions commonly included in the prenatal screening panel include:

- Trisomy 18

- Trisomy 13

- Trisomy 16

- Trisomy 22

- Triploidy

- Sex chromosome aneuploidy, such as Turner syndrome and Klinefelter’s syndrome (47, XXY)

- Certain disorders caused by a chromosomal deletion (microdeletion syndrome), such as Prader-Willi syndrome and Jacobsen syndrome

- Certain single-gene disorders associated with abnormalities of the skeleton or bones, such as sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis

Therefore, we will give a basic overview of a few conditions commonly included in the non-invasive prenatal screening panel and also address some outdated information related to those conditions to emphasize the importance of staying up-to-date about all conditions.

Keep in mind that the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics does not recommend NIPS to screen for autosomal aneuploidies other than those involving chromosomes 13, 18, and 21, and ACMG advises clinicians to inform patients that there are increased chances for false-positive results for the other conditions caused by sex chromosome aneuploidies and copy number variants (CNVs).

References

Gregg AR, Gross SJ, Best RG, et al. ACMG statement on noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy. Genet Med. 2013;15(5):395–398

Basic Phenotype and Psychosocial Aspects of Genetic Conditions

If we look at the basic phenotype of people with Down syndrome, it hasn’t changed much over the past 50 years. Most people with Down syndrome have common physical characteristics. They are also usually shorter than average. They commonly have low muscle tone, increased chances for various health conditions (such as heart defects and gastrointestinal issues), and mild to moderate intellectual disabilities. About 250,000 people in the US have Down syndrome, and about 1 in 800 babies are born with the condition.

Introduction to the Course and History of Disability Rights

Over the past 50 years, the outcomes for people with disabilities has evolved significantly through access to better healthcare, supports and services, and educational and community inclusion. These developments over time are what make it so vital for clinicians to have access to the most up-to-date and accurate information available for different genetic conditions currently included in the prenatal screening panel. The information given at the moment of diagnosis can shape perceptions for a lifetime and significantly impact families.

Click on the first topic below to get started.

Lesson: Concluding Thoughts Copy

When a couple is told there is a positive diagnosis for Down syndrome before a baby is born, it is very important for the physician to recognize the complex feelings that they have at this moment. Since the definitive diagnosis may also occur during the second trimester (though in the above case, it actually occurred in the first trimester), couples may have already developed ideas about what this particular baby will be like. A diagnosis of Down syndrome obviously alters that perception and leaves parents with conflicted emotions. Many couples will want to continue the pregnancy, no matter what, but may be afraid of what their future will bring. Others may believe that they will not be able to care for a child with Down syndrome, but are uncertain about specifics regarding termination. Still others may be torn about both options, knowing that their lives will be altered with any decision they make. Most will not know about adoption options.

Recognizing that physicians and other health care practitioners will have their own biases about what should be done, each medical provider (physicians, genetic counselors, nurses, physician assistants, etc.) needs to respond as a member of a coordinated team to individual patients in ways that reflect the patient’s values. Physicians should respond with empathy and concern as well as specific information. This type of conversation might include reference to new understandings about improved life outcomes for individuals with Down syndrome, such as their capacity to learn and become a contributing part of the larger community, and referral to local Down syndrome organizations. It also might include information on organizations devoted to adopting children with Down syndrome. However the physician or health care provider responds, the mother and father should feel understood, supported, and informed.

Your interactions with families such as this one will be remembered by them for the rest of their lives.

Thank you for taking the time to carefully consider your responses to these cases. We hope this module helps you as you assist other families in receiving this news.

Lesson: Delivering Test Results Copy

Two weeks have passed. Mrs. Abbott decided to have a transcervical CVS near the end of the 12th week of her pregnancy. The results of the test confirm that the baby has Down syndrome. During the following interview, Dr. Thomas will share the results of the CVS with both Mr. and Mrs. Abbott, and discuss with the Abbotts the options they have for this pregnancy.

Lesson: Screening and Testing Copy

It is now six months later. Mrs. Abbott has conceived and is now in her 11th week (gestational age estimated at 11 weeks, 3 days). She is seeing Dr. Thomas for the third time in her pregnancy. As was outlined in their discussion in Lesson 1, Dr. Thomas offered a diagnostic or confirmatory test (chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis). Mrs. Abbott first elected to have a screening test, in this case the first trimester screening test of nuchal translucency in conjunction with serum protein analytes. They will discuss the results of the screening during this visit. Mr. Abbott has accompanied Mrs. Abbott to this visit.

Best Practices for Communicating a Prenatal Diagnosis of Down Syndrome – Case Study

Communicating a prenatal or postnatal diagnosis or screening test results to a family can be overwhelming for both the clinician and the patient. That moment is often described as a flashbulb memory that a patient remembers in detail for a lifetime. Fortunately, best practice recommendations outline suggestions for discussing a prenatal or postnatal diagnosis so that clinicians can frame that moment in sensitivity and compassion (Skotko et al., 2009; Sheets et al., 2011). It’s also important to remember that patients consider the moment they receive screening test results and also the moment when they receive diagnostic results as part of their diagnosis journey.

Best practice guidelines for communicating a prenatal or postnatal diagnosis include the following recommendations (Skotko et al., 2009):

- Clearly outline the differences between prenatal screening and diagnostic tests. Importantly, patients need to understand that screening tests (including cell-free DNA and non-invasive prenatal screening tests) indicate a patient’s chances for having a baby with a number of genetic conditions. However, the screening tests are not definitive because false positives do sometimes occur. Only chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis are considered diagnostic. (Gregg, 2013)

Note: If screening results indicate that the fetus likely has a condition, you need to make sure expectant parents understand that the results are not conclusive, but the majority of parents want condition-specific information right away. If they do not receive that information from their clinician, they will likely perform an online search on their own. Moreover, many parents will still decline diagnostic testing and will not receive any information if your policy is to wait on giving condition-specific information until after diagnostic confirmation. - If a pregnant woman wants to undergo testing, ask her about why having a diagnosis prior to birth would be important to her. This can help better guide any future conversations about a test result.

- When possible, deliver the results in person or at a pre-established time by phone. Determine a standard way of handling all results and tell patients about that up front so that they don’t get the impression that an appointment or phone call is only scheduled if results indicate a diagnosis.

- Personally deliver the diagnosis as soon as possible following definitive prenatal testing. Use commonly understandable terms and convey information in a patient’s native language, when translation is available.

- Each condition detected with prenatal testing has different outcomes, and each expectant parent reacts differently based on his or her background and experience, life circumstances, and perceptions about parenting. Assess the emotional reactions of the expectant parents, and validate these feelings. Use active listening and empathetic responses to offer support. (Sheets et al., 2011)

- If a condition does not cause premature death, use neutral language such as, “The results indicate…” and not begin with, “I’m sorry,” or“Unfortunately, I have some bad news…”

- Provide accurate and up-to-date information about the genetic condition and contact in- formation for local support organizations.

Resources

- Delivering a Prenatal or Postnatal Diagnosis (You can request a free printed copy)

References

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gyne- cologists. (2007). ACOG Practice Bulletin Num- ber 77. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 109:217-225.

Gregg, A.R., Gross, S.J., Best, R.G., Monaghan, K.G., Bajaj, K., Skotko, B.G … Watson, M.S. (2013). ACMG statement on noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy. Genetics in Medicine, 15:395-398.

Levis DM, Harris S, Whitehead N, et al. Women’s knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about Down syndrome: A qualitative research study. Am

J Med Genet Part A 2012;158A:1355–1362.

Sheets, K.B., Feist, C.D., Sell, S.L., Johnson, L.R., Dona- hue, K.C., Masser-Frye, D., … Brasington, C.K. (2011). Practice Guidelines for Communicating a Prenatal or Postnatal Diagnosis of Down Syndrome: Rec- ommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Counsel, Oct;20(5):432-41.

Skotko, B.G., Kishnani, P.S., Capone, G.T. for the Down Syndrome Diagnosis Study Group. (2009). Prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome: How

best to deliver the news. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 149A(11):2361-7.

Other Conditions Copy

Pregnancy screening tests do not exclusively look for Down syndrome, and they usually include a number of other conditions. Some conditions commonly included in the prenatal screening panel include:

- Trisomy 18

- Trisomy 13

- Trisomy 16

- Trisomy 22

- Triploidy

- Sex chromosome aneuploidy, such as Turner syndrome and Klinefelter’s syndrome (47, XXY)

- Certain disorders caused by a chromosomal deletion (microdeletion syndrome), such as Prader-Willi syndrome and Jacobsen syndrome

- Certain single-gene disorders associated with abnormalities of the skeleton or bones, such as sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis

Therefore, we will give a basic overview of a few conditions commonly included in the non-invasive prenatal screening panel and also address some outdated information related to those conditions to emphasize the importance of staying up-to-date about all conditions.

Keep in mind that the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics does not recommend NIPS to screen for autosomal aneuploidies other than those involving chromosomes 13, 18, and 21, and ACMG advises clinicians to inform patients that there are increased chances for false-positive results for the other conditions caused by sex chromosome aneuploidies and copy number variants (CNVs).

References

Gregg AR, Gross SJ, Best RG, et al. ACMG statement on noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy. Genet Med. 2013;15(5):395–398

Life Outcomes Copy

Next, we will explore how improved social support and services have impacted different areas of life for people with Down syndrome. While we are looking at Down syndrome specifically, many of these principles can also be applied to other genetic conditions as well.

Basic Phenotype -Comparing Clinician & Patient Top Concerns Copy

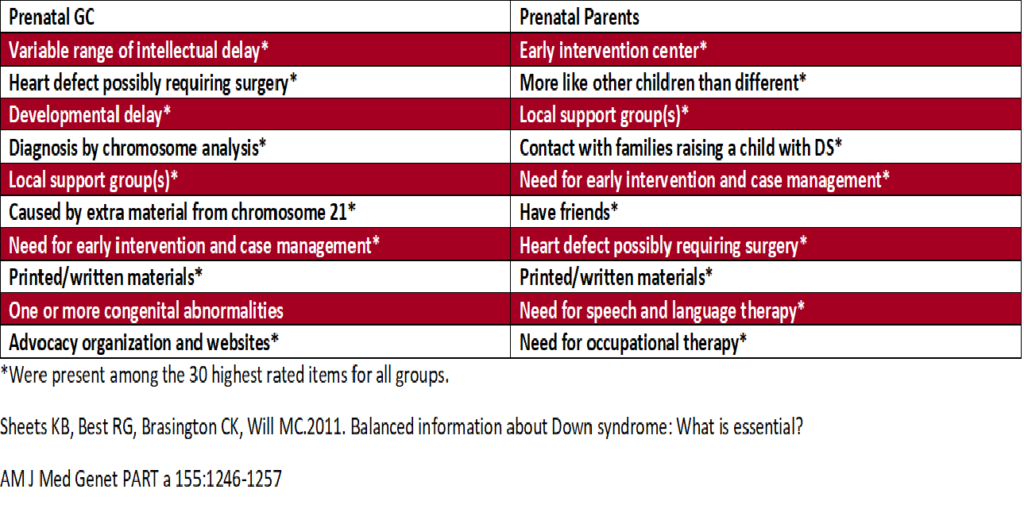

Families and clinicians sometimes differ on what kinds of information are most important to them beyond that basic phenotype. The chart below, based on research by Katie Berrier, shows the top ten priorities identified by parents who receive a prenatal diagnosis and genetic counselors delivering a prenatal diagnosis. Clinicians tend to value genetic and health information while families are more concerned about available supports and social implications; however, they both value the importance of printed/written materials.

Historically, clinicians have tended to favor what is called a “medical model” of disability which frames disabilities in the context of the medical problems associated with them. While these medical issues are important to address for health reasons, there is a social model of disability which suggests that many of the challenges associated with disabilities can be addressed with better support, services, and social attitudes.

In comparing the information viewed as most important by genetic counselors and parents, you can see the interplay of both of those models.

References:

Sheets KB, Best RG, Brasington CK, Will MC. Balanced information about Down syndrome: What is essential? Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155:1246–1257

Basic Phenotype Description Copy

If we look at the basic phenotype of people with Down syndrome, it hasn’t changed much over the past 50 years. Most people with Down syndrome have common physical characteristics. They are also usually shorter than average. They commonly have low muscle tone, increased chances for various health conditions (such as heart defects and gastrointestinal issues), and mild to moderate intellectual disabilities. About 250,000 people in the US have Down syndrome, and about 1 in 800 babies are born with the condition.

Disability Rights Timeline Copy

Learn about how progress for disability rights—through implementation of laws and support services—has improved outcomes for people with Down syndrome and other genetic conditions.

Introduction Copy

Over the past 50 years, the outcomes for people with disabilities has evolved significantly through access to better healthcare, supports and services, and educational and community inclusion. These developments over time are what make it so vital for clinicians to have access to the most up-to-date and accurate information available for different genetic conditions currently included in the prenatal screening panel. The information given at the moment of diagnosis can shape perceptions for a lifetime and significantly impact families.

Learn about how access to supports and services, good healthcare, inclusion (and the lack thereof) significantly shaped the outcomes for two generations in one family.